zurück zur Gedicht- übersicht |

|

Hebel-Gedichte - hochdeutsche und englische Übersetzung | |||||

| Der Schmelzofen | Der Schmelzofen | The melting furnace | |||||

|

|

|

( Gespräch in der Weserei*, einem Hausener Gasthaus ) Jetzt brennt er in der schönsten Art, bis das Wasser rauscht, der Blasebalg knarrt, und bis dann die Nacht vom Himmel fällt, dann wird die erste Massel kalt. Und das Wasser rauscht, der Blasebalg knarrt; ich habe daraufhin einen Gulden gespart, Gang, Kunigunda, lang uns alten Wein, wir wollen ein wenig lustig sein! Eine Freudenstunde ist nicht verwehrt; man geniesst mit Dank, was Gott beschert, man trinkt einen frischen, frohen Mut, und drauf schmeckt wieder das Schaffen gut. Eine Freudenstunde, eine gute Stunde! sie erhält Leib und Kräfte gesund; doch muss es in der Ordnung gehen, sonst hat man Schande und Leid davon. Ein froher Mann, ein rechtschaffener Mann! Jetzt schenkt ein und stoßt an: "Es lebe der Markgraf und sein Haus!" Zieht die Kappen aus und trinket aus! Einen besseren Herrn trägt die Erde nicht, es ist ein Segen, was er tut und gibt, ich kann es nicht sagen, wie ich es sollte, danke es ihm Gott! Danke es ihm Gott! Und das Bergwerk soll im Segen stehen! es hat mancher Bürger das Brot davon. Der Herr Inspektor langt in den Trog und zahlt mit Freude, es ist keine Frage. Darum schenkt ein und stoßt an! Der Herr Inspektor ist ein Mann, mit unseren geschickten Leuten von gleich zu gleich, und freundlich gegen groß und klein. Er schafft einen guten Wein aufs Werk, er holt ihn über Tal und Berg, und stellt ihn lauter auf den Tisch und misst, wie es recht und billig ist. Das ist von je her so: der Mann am Feuer muss zu trinken haben, wäre es noch so teuer. Es rieselt mancher Tropfen Schweiß, und will es nicht gehen, man ächzt deshalb. Man streift den Schweiß am Ärmel ab, man schnauft; die Bälge erstaunen deshalb, und manche liebe Mitternacht wird so am heißen Herd durchwacht. Der Schmelzer ist ein geplagter Mann, darum bring es ihm einer, und stößt an: Segne Gott! Vergiss deinen Schweiß und deine Mühe! es hat jeder andere auch seine Sache. Am Zahltag teiltest du doch mit keinem; und bringst den Lohn im Taschentuch heim, so schaut dich die Maria freundlich an, und sagt: "I habe einen rechtschaffenen Mann!" Darauf schlägt sie Eier mit Butter ein, und streut ein wenig Ingwer dran; sie bringt Salat und Speck dazu, und sagt: "Jetzt iss, du lieber Mann" Und wenn ein Mann seine Arbeit tut, so schmeckt ihm auch sein Essen gut. Er tauscht nicht ein in Leid und Liebe mit manchem reiche Galgen-Dieb. Wir sitzen hier, und es schmeckt uns wohl. Geh, Kunigunda, hol noch einmal, weil doch der Ofen wieder geht, und das Erz in vollen Kübeln steht! So brenne er denn zu guter Stunde, und Gott erhalte euch alle gesund, und Gott bewahre euch auf der Schicht, dass niemand Leid und Unglück geschieht! Und kommt in strenger Winters-Zeit wenn Schnee auf Bergen und Firsten liegt, ein armer Bub, ein armer Mann, und stellt sie ans Feuer und wärmt sie daran. und bringt ein paar Kartoffeln und legt sie ans Feuer und bratet sie und schlaft beim Setzer auf dem Erz - schlaf wohl, und tröste dir Gott dein Herz! Dort steht so einer. Komm, armer Mann, und gib uns Bescheid, wir stoßen an! Segne Gott, und tröste Gott dir dein Herz! Man schläft nicht lieblich auf dem Erz. Und kommt zur Zeit ein Biedermann ans Feuer, und zündet das Pfeifchen an, und setzt sich irgendwo mit dazu dann schmecke es ihm wohl, und - brenn dich nicht! Doch fängt ein Bübchen zu Rauchen an, und meint, es könne es wie ein Mann, dann macht der Schmelzer kurzen Prozess, und zieht ihm das Pfeifchen aus dem Gesicht. Er wiirft es ins Feuer, und schimpft dazu: Hast du es auch schon gelernt, du Dummkopf du! Saug an einem Stengel Hafermark, Weist du? Hafermark macht Buben stark!" es ist wahr, es gibt manche Kurzweil mehr am Sonntag nach der Kinderlehre; und strömt der feurige Eisen-Bach im Sand, es ist eine schöne Sache. Frag manchen Mann: "Sag, Nachbar, he! hast du auch schon Eisen werden sehn im feurigen Strom den Formen nach?" Was gilt es, er kann nicht sagen: Ja! Wir wissen, wie man das Eisen macht, und wie es im Sand zu Masseln bäckt, und wie man es darauf in die Schmiede bringt, und die Luppen unter dem Hammer zwingt. Jetzt schenkt ein und stoßt an: Der Hammermeister ist ein Mann! Wären Hammer-Schmied und Korbflechter nicht, da läge eine Sache, was täte man damit?' Wie ginge es dem braven Handwerks-Mann? es muss jeder Stahl und Eisen haben; und es muss den Schneider Nadeln geben, sonst ist es um seine Nahrung geschehen. ' Und wenn im frühen Morgenrot der Bauer in Feld und Furchen steht, dann muss er Hacke und Pickel haben, sonst ist er ein verlorener Mann. Zum Pflügen braucht er die Pflugschar, zum Mähen die Sense, und die Sichel, wenn der Weizen bleicht, und das Messer, wenn die Traube reift. So schmelzt denn, und schmiedet ihr, und dank euch Gott der Herr dafür! Und mache ein anderer Sicheln daraus, und was man braucht in Feld und Haus! Und nur keine Säbel mehr! es hat Wunden genug und Schmerzen gegeben, und es hinkt ein mancher ohne Fuß und Hand, und mancher schläft im tiefen Sand. Keine Kanonen, keine Gewehre mehr! Mann hat die heftigen Klagen etwa gesehen, und gehört, wie es in den Bergen kracht, und Ängste gehabt die ganze Nacht. Und gelitten haben wir, was man kann, darum schenkt ein, und stoßt an: Auf Völker-Friede und Einigkeit von nun an bis in Ewigkeit! Jetzt zahlen wir! Jetzt gehen wir heim, und schaffen heut noch allerlei, und dengeln noch bis tief in die Nacht, und mähen, wenn der Tag erwacht.

|

( Conversation in the Weserei*, an inn in Hausen ) Now it burns in the most beautiful way, until the water rushes, the bellows creak, and until the night falls from the sky, then the first ingot gets cold. And the water rushes, the bellows creak; I have saved a guilder, Gang, Kunigunda, long us old wine, Let's have a little fun! An hour of joy is not denied; one savours with thanks what God has given, we drink a fresh, cheerful courage, and then the work tastes good again. An hour of joy, a good hour! It keeps body and strength healthy; but it must be done in order, otherwise you will suffer shame and sorrow. A happy man, a righteous man! Now pour and toast: ‘Long live the margrave and his house!’ Take off your caps and drink up! The earth has not borne a better lord, It is a blessing what he does and gives, I cannot say it as I should, thank him God! Thank him God! And the mine should be blessed! Many a citizen's bread is buttered by it. The inspector reaches into the trough and pays with joy, it's no question. So pour and toast! The inspector is a man, with our skilful people from equal to equal, and friendly to big and small. He brings good wine to the work, he fetches it over valley and mountain, and puts it loudly on the table and measures it out as is right and fair. It has always been so: the man by the fire must have a drink, however expensive it may be. Many a drop of sweat trickles down, and if it won't go, you groan. You wipe the sweat off your sleeve, you snort; your bellows are astonished, and many a dear midnight is woken up like this at the hot cooker. The smelter is a troubled man, so someone brings it to him and toasts: Bless God! Forget your sweat and toil! Everyone else has his own business. On payday you share with no one; and bring your wages home in a handkerchief, Mary looks at you with joy, and says, ‘I have a righteous husband!’ Then she beats eggs with butter, and sprinkles a little ginger on top; She adds lettuce and bacon, and says: ‘Now eat, you dear man’ And when a man does his work, his food tastes good too. He does not trade in suffering and love with many a rich gallows thief. We're sitting here and we're enjoying ourselves. Go, Kunigunda, fetch again, because the oven is going again, and the ore is in full buckets! So let it burn at a good hour, and God keep you all well, and God keep you on the shift, that no one suffers harm or misfortune! And come in the harsh time of winter When snow lies on mountains and ridges, a poor boy, a poor man, and puts them by the fire and warms them. And brings a few potatoes and puts them by the fire and roasts them and sleep on the ore with the setter - Sleep well, and God comfort your heart! There stands such a one. Come, poor man, and let us know, we'll make a toast! Bless God, and God comfort your heart! One does not sleep sweetly on the ore. And at this time of the year, a bourgeois To the fire, and lights his pipe, and sits down somewhere with it then enjoy it, and - don't burn yourself! But a little boy begins to smoke, and thinks he can do it like a man, then the smelter makes short work of him and pulls the pipe out of his face. He throws it into the fire and scolds him: Have you learnt it yet, you fool! Suck on a stalk of oatmarrow, Do you know? Oatmarrow makes boys strong!" It's true, there are many more amusements on Sunday after the children's lesson; and if the fiery iron brook flows in the sand, it's a beautiful thing. Ask some men: ‘Say, neighbour, hey! Have you seen iron become iron in the fiery stream after the moulds?" What does it matter, he can't say: Yes! We know how to make iron, and how to bake it into ingots in the sand, and how to bring it to the forge, and force the hollows under the hammer. Now pour and toast: The hammer master is a man! If it weren't hammer smith and basket maker, there was one thing, what would you do with it?' How would the good craftsman fare? Everyone must have steel and iron; and there must be needles for the tailor, otherwise his food is gone. ' And when in the early dawn the farmer stands in field and furrow, then he must have hoe and pickaxe, otherwise he is a lost man. For plowing, he needs the ploughshare, the scythe for mowing, and the sickle when the wheat bleaches, and the knife when the grapes ripen. Melt then, and forge ye, and thank the Lord God for it! And make another sickle out of it, and whatever you need in field and house! And no more sabres! There have been enough wounds and pain, and some limp without foot or hand, and many a man sleeps in the deep sand. No more cannons, no more rifles! Man has seen the fierce lamentations, and heard how it crashes in the mountains, and had fears all night. And we have suffered what we can, therefore pour and toast: To the peace and unity of nations From now until eternity! Now we pay! Now we go home, and do all sorts of things today, and we'll iron deep into the night, and mow when the day awakens. |

||||

|

*

gemeint ist das als Verweserei = Verwaltung des Eisenwerks dienende "Herehus", das auch eine Art Gasthaus, die "Betriebskantine" enthielt. Maßle = Masseln sind eine erstarrte Schmelze mit dem Zweck, eine leicht transportfähige und handhabbare Zwischenstufe für eine spätere Verarbeitung zu sein. Hurlibaus = Name einer historischen Kanone der Stadtverteidiung Schopfheims, die schon zu Hebels Schulzeit an der Lateinschule existierte (und heute noch beschussfähig ist).

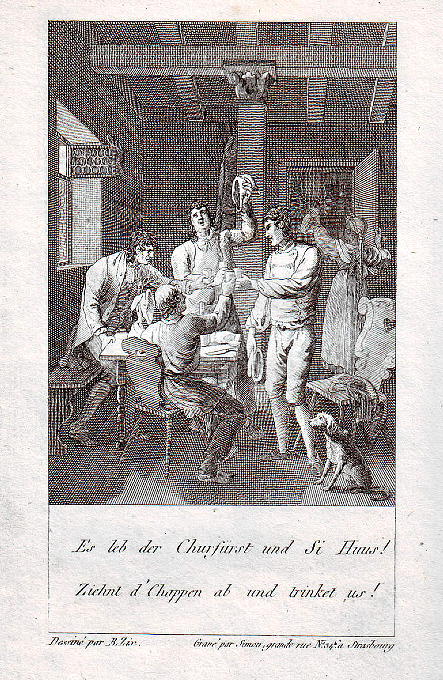

Kupferstich zum Gedicht

|

Kupferstich: Benjamin Zix, Straßburg

|

* This refers to the “Herehus”, which served as the ironworks administration and also contained a kind of inn, the ”company canteen”.

Maßle = ingots are a solidified melt Hurlibaus = name of a historical cannon used

Copperplate engraving for the

|

|||||

„Ohne Gold kann man leben, ohne Eisen

nicht".

|

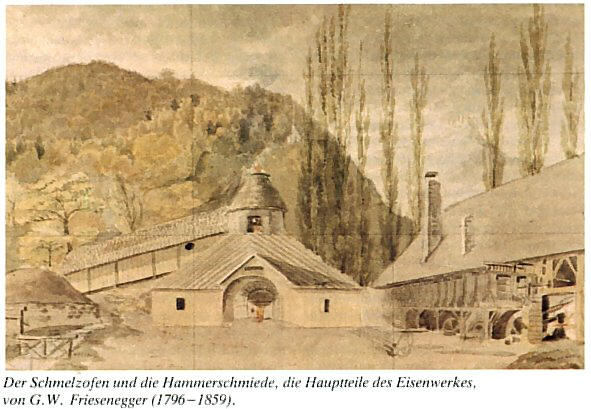

1 - Schmelzofen = Hochofen 1 - Melting furnace = blast furnace |

‘You can live without gold, but not

without iron’. Margrave Karl Friedrich von Baden also realised this - there was no gold in his treasure chest, but there was plenty of iron ore in the soil of the Markgräflerland. The margrave and the bailiff of Lörrach therefore endeavoured early on to establish an iron industry. The location of Hausen on the Wiese (providing water power) and near the Black Forest (providing charcoal for the smelting process) was ideal. The foundations for the smelting furnace were laid on 7 March 1682 and the fire for the first casting was lit on 3 April 1684. The blast furnace was usually in continuous operation for 12 to 14 months at a time for iron production - a so-called ‘smelting journey’. The ironworks initially changed the image and structure of the village little in the course of its long existence. The employees of the works, called ‘Laboranten’ (from the Latin 'labore' = to work), lived for the most part ‘ufem Bergwerch’ in the Laborantenhäuser, some of which still exist today. Over the course of the following 180 years until the final closure of the ironworks, however, the structure of the village changed permanently. A significantly different stratification of the population was brought about, because in addition to the factory workers with their differentiated division of labour, blacksmiths, nail, chain and tine smiths settled here. In the 18th century, a pipe forge for gun barrels and even a gun factory with a gunsmith from Karlsruhe were set up for a short time. The factory was shut down in 1865: - the Black Forest was largely deforested and no longer supplied charcoal - against cheap imported iron, especially from England, the price of Hausen iron was no longer competitive - In the course of the industrial revolution, the plants relocated to industrial centres with good transport links and a large supply of energy and labour (e.g. Ruhr area and Saarland) |

|||||

zurück zur Gedicht- übersicht

|

Übersetzung in Hochdeutsch: Hansjürg Baumgartner Übersetzung in Englisch: DeepL (free version) |

||||||